What Is Bulimia?

Anorexia's Destructive Twin

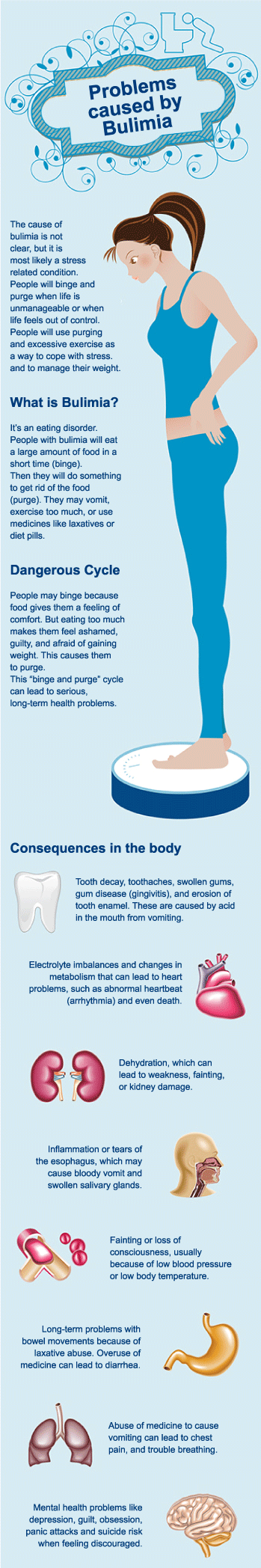

The primary feature of bulimia nervosa is the frequent episodes of binge-eating associated with feelings of loss of control. Once begun, the individual feels unable to stop eating until an excessive amount of food has been consumed. This loss of control is only subjective, since most individuals with bulimia nervosa will abruptly stop eating in the midst of a binge episode if interrupted.

After overeating, individuals with bulimia nervosa engage in some form of purging or other extreme behavior in an attempt to avoid weight gain. Most patients with this syndrome report self-induced vomiting or the abuse of laxatives. Other methods include misusing diuretics, fasting for long periods, and exercising extensively after binge eating. It is important to note that complications from BN and AN (Anorexia Nervosa) can potentially affect every organ system.

Bulimia nervosa comes in second to anorexia as a main cause of death for eating disordered teens with a rate of about 5% at 10 years. Usually, people don't connect compulsive exercise, purging, diuretics, and/or laxatives with death. Many bulimics will die of an esophageal hemorrhage or a heart attack.

The following lists are compiled from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, V.

The current DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa are:

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterised by both of the following:

· Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances. ·A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). - Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviour in order to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications, fasting, or excessive exercise.

- The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviours both occur, on average, at least once a week for three months.

- Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.

- The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of Anorexia Nervosa.

As with AN (Anorexia Nervosa), BN (Bulimia Nervosa) has a myriad of medical problems associated with the disease. However, unlike AN, bulimics see their problems as out of control and will tend to try to stop (vs. trying to hide it as in AN). The psychological problems are similar to that of AN; problems with families and expression of feelings, loss of control, low self- esteem and depression (Williamson, Barker & Norris, 1994). Physical findings with patients of BN are important in diagnosis and in treatment, as with AN.

Medical Findings Associated with Bulimia Nervosa

- Bruised or abraded knuckles (Russell sign)

- Facial Ecchymoses (blood under the skin)

- Conjunctival hemorrhages

- Pharyngitis

- Dental enamel erosion

- Menstrual irregularities

- Esophagitis

- Esophageal erosions and ulcerations

- Esophageal rupture

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Crampy abdominal pain

- Acute gastric dilation (with binge)

- Constipation

- Pancreatitis

- Hypokalemia

- Hypomagnesemia

- Hyponatremia

- Brachycardia (slow heartbeat)

- Low voltage, prolonged QT interval (heartbeat timing)

- Parotid and salivary gland swelling

Approximately 10% of women in western countries will be diagnosed with an eating disorder at some point in their lives, making it one of the more prevalent psychiatric problems faced by women. The lifetime prevalence for BN is approximately 2% for women (Stice, Telch, & Rizvi, 2000). Current estimated lifetime female risk for bulimia is about 8% (Kendler, MacLean, Neale & Kessler, 1991). However, like AN, there are studies that show sharply increased prevalence rates for special populations, such as college students ( 4.5% to 18%) (Turnbull, Ward & Treasure, 1996) or (19%) (http://womensissues.about.com/library/bleatingdisorderstats.htm). Some research indicates that as many as 33% of college students experiment with eating disordered behaviors but that only 18-20% will go on to develop clinical eating disorders. The reports of relapse rates are mixed. One study reported a 63% probability of relapse after 78 weeks (Keller, Herzog, Lavori & Bradburn, 1992).

Many of these bulimic patients have co-morbid psychiatric disorders including obsessive-compulsive disorder, mood disorders, and substance use disorders. Preliminary studies of BN have found that 5 to 10 years after initial presentation, 20% continue to meet full diagnostic criteria (Keel, 1997). At Mirasol, major depression and anxiety disorders are present in the vast majority of our patients. Forty percent of all women with an eating disorder also have substance abuse issues.

BN normally begins later in life than AN (around ages 17 to 25) and may occur in individuals with a history of AN (Williamson, Barker & Norris, 1994). A model exists in the literature that suggests that overeating causes extreme anxiety, which is relieved by purging. The purging 'undoes' the effects of the binging, much like compulsive rituals of handwashing, and is therefore, negatively reinforced in the same manner as compulsive rituals. The cycle then becomes habitual. However, many other studies have found significant psychopathology in BN subjects and their families. Bulimic patients tend to come from families with conflict resolution problems and tend to experience low control within the family system (Herzog, Keller, Lavori & Gray, 1992). Fairburn et al. (1993) found that residual attitudinal disturbance, particularly in regard to body image, predicted treatment outcome. They found that, the greater the disturbance, the more dismal the outcome and a clear linear relationship existed between the two.